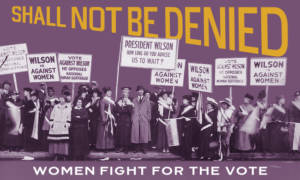

18 Aug Women and the Vote: Hope Rests in Tennessee

Republican Convention

On June 8, 1920, the Republicans opened their convention in Chicago. Thirty-five states had ratified the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, with one remaining state needed for the amendment to become law. The Woman’s Party picketed the convention with signs like

“The Republican Convention Has the Power to Enfranchise Women. Will They Do So?”

“Vote Against the Republican Convention as Long as It Blocks Suffrage.”

Vermont and Connecticut were the only Republican states left whose legislatures had not voted on ratification. At the end of the convention, the two states had not yielded to pressure and had not convened their legislatures.

Democratic Convention

On June 15, Louisiana defeated ratification in its regular session. The North Carolina legislature was scheduled to meet in August, with little hope of ratification.

When the Democratic National Convention convened in San Francisco on June 28, Tennessee and Florida were the last two possible Democratic states to ratify. State election laws prohibited both legislatures from acting upon a federal amendment unless a new election was held between the federal passage and its ratification. This was the equivalent of requiring a state referendum. Under these circumstances, it would be impossible for either state to ratify in time for women to vote in the 1920 election.

Ratification an Act of the State Legislature

Then, a court case in Ohio decided that ratification was an act of the state legislature and was not subject to referendum. Lawyers pointed out that the clause in the Tennessee Constitution was equal to requiring a referendum. Since the Ohio case had rendered a referendum on such a matter illegal, the Tennessee law could not stand in the way of ratification by the existing legislature.

The Democrats seized on the opportunity and submitted a resolution to Governor Roberts of Tennessee to call a special session. The president sent a letter as well. Governor Roberts announced that he would call the session on August 9.

Anyone can imagine the excitement and anticipation of the Suffragists, as they rested their last hope in Tennessee.

The following is a fictional account of what it must have been like for women suffragists, as they participated in this last effort to pass the Nineteenth Amendment in time for women to vote in the November 1920 election.

In the Fullness of Time: One Woman’s Story of Growth Empowerment

Chapter 25: Hope Rests in Tennessee

by Katherine P. Stillerman

“Get your bags packed. We’re going to Tennessee to work for ratification,” Alice said on the other end of the line.

“Pauline and I will be by to get you in the morning. We had a call from Bonnie Swift, and she said she’d meet us in Nashville and we can stay with the volunteers from Jackson at her mother’s house. Bonnie has plenty of room. She said we carried the Tennessee banner for her back in 1913, and now she wants us to come up there and help them carry it through to passage.”

“Oh, Alice,” said Hattie, “there’s nothing I’d rather do, but I’m seven months pregnant, and there is no way Charles would agree for me to travel that far.”

“I know. I thought as much, but I had to give it a try. We’ll call you every night and give you a full report on everything that’s going on.”

“Say hello to Bonnie. She was so sweet to call with condolences when the South Carolina legislature defeated the amendment,” said Hattie.

On August 9, Alice called to give Hattie the first report.

“Well, we are in Nashville, and it’s a madhouse. Suffragists and Anti-Suffragists have set up headquarters, along with the lobbyists for the railroads, the manufacturers, and the corporations. You can tell how high the stakes are, because every possible interest group has some kind of representation.”

“Does it look like they’ll have enough votes to ratify?”

“It seems like the purple and gold of the Suffragists outnumber the red roses of the Anti-Suffragists, but it’s really hard to tell at this point. Some of the legislators seem to be changing their minds, saying they doubt the constitutionality of the session.

They worry that it may be illegal based on the state constitution. Even the speaker was hedging a bit today. He had formerly said the session was constitutional and that he would vote yes, but today he has changed his mind.

Alice Paul has summoned the best legal minds in the country to be on hand to assure the legislators of the legality of the session. She doesn’t want them to have any excuse not to vote yes.”

“Well, I’m sure that Miss Paul also has a master plan for getting the votes. Hold the party in power responsible! That has always been her tactic. And now that both parties share a stake in the power, she can play them against each other, creating a virtual footrace to see who can deliver the final state by November.”

“That’s the plan. Keep your fingers crossed that it will work, and I’ll call you when there’s more news.”

“Alice? Are you still there?” Hattie asked. There was no response.

It had been three days since Alice called, and Hattie was getting nervous. Finally, the phone rang, and Alice began talking in her usual manner without saying hello first.

“Good news! It passed in the Senate, twenty five to four.”

“Alice, that’s wonderful. I was about to have apoplexy from wanting to hear from you.”

“I know, but we’ve been working night and day to keep track of the votes. We meet every few hours to compare our numbers and to make sure we have an accurate tally.” The ratification had been introduced the day before in both the House and the Senate. It was immediately referred to the committees. A joint meeting of both committees assembled in the hall of the capitol.

“Today it passed in the Senate, and now the big challenge will be to get it through the House,” said Alice.

“Do you think you’ll have the votes?”

“I hope so, but the Anti-Suffragists are doing everything they can to persuade the legislators to vote no. They know that a number of them are only agreeing to vote yes because of the pressure coming from the national party leaders. When they saw the amendment would pass the Senate, they began to introduce measures that would be tantamount to defeat.”

“What kind of measures?”

“One proposed that the question of ratification should be referred to mass meetings of the people to be held in every district on August 21. Of course that would have meant postponement so that women could not vote in the 1920 election. But the anti-suffragist group is clever, and they knew their proposal would give the uncertain legislators a way to straddle the fence.”

“I assume that did not pass.”

“No, it was tabled when the Woman’s Party sent a clear message to the leaders of each party that they considered the proposal hostile to suffrage and would hold them responsible if it passed.”

“How do the votes look now?”

“The vote was forty-eight forty-eight to table the resolution, so we assume that’s how the ratification vote would go. We figure we need at least one more legislator to commit to vote yes.”

“Can you get one more?”

Alice explained there were two possibilities. Representative Banks Turner, the Republican chairman, indicated he could be counted on, but continued to wear the red rose of the Anti-Suffragists even though he voted to table the amendment. He had stated repeatedly that he could not pledge himself, but would do nothing to hurt the suffrage cause. The Woman’s Party thusly assumed he would abstain, which would make the vote forty-eight forty-seven in favor of ratification.

Representative Harry Burn, twenty-four, and the youngest member of the legislature, had been unwilling to commit either way. He was a good friend of Speaker Roberts, who was under intense pressure from Democratic presidential nominee Cox to deliver the needed votes for ratification.

“He’s young and has been besieged by the Anti-Suffragists, who persuaded him to vote not to table the amendment. We understand that Representative Burn’s mother is an ardent suffragist, and she has written him a letter instructing him to vote yes.”

“Poor man,” said Hattie. “He’s in a real quandary. But I hope he listens to his mother.”

“You know we’ll milk that for all it’s worth. I’ll keep you posted, but I may not be able to call until it’s all over. They think the vote will come up in the next few days, and all the volunteers have been put on alert to be available around the clock. I think Pauline and I will stay over at the Woman’s Party headquarters if there is room, so we can be in walking distance of the capitol.”

“I wish I could be there with you! I’ll never forget the 1913 suffrage parade or the day we started the Calhoun Equal Suffrage League or our march around the White House in the pouring rain or our trip to New York. And now the end of our struggle for suffrage may be in sight, and I’d give anything to witness it.”

“You’re right where you need to be, taking care of my soon-to-be niece or nephew. Let’s just hope we can get this thing ratified so that baby’s mother can cast her first vote before he or she comes into the world.”

Hattie started to respond, but the phone had gone dead.

On August 18, 1920, the phone in the Bartons’ kitchen rang, and Hattie’s heart just about jumped out of her chest. It had been five days since Alice had called, and she had been on pins and needles waiting to hear something. She had tried to stay busy, helping Georgia with the canning, washing and pressing the little clothes in the baby’s layette, and catching up on her correspondence.

But her mind had been all the way in Nashville, Tennessee, trying to visualize Alice and Pauline and Bonnie Swift and all the other Woman’s Party volunteers working around the clock, leaving no stone unturned in their effort to win the final vote needed for ratification.

Had they succeeded in securing that one last vote? Had Representative Banks Turner kept his promise to do nothing to hurt the suffrage cause? Had Representative Harry Burn been a dutiful son and voted yes as his mother instructed? Or would their hopes be dashed once again because the anti-suffragist sentiments had prevailed, as they had back in January when South Carolina defeated ratification?

“Oh, Charles, you answer it. I don’t think I can stand it if it’s bad news.”

Charles picked up the receiver as Hattie hovered over him. He listened for a moment and then handed the receiver to Hattie.

“I think you’re going to want to hear this.”

As Hattie put the receiver to her ear, she could hear cheering and clapping and chanting in the background. Alice was almost yelling into the receiver. “Put on your voting shoes, Hattie. The Tennessee legislature has passed the suffrage amendment forty-nine to forty-seven. Both Harry Burn and Banks Turner voted yes!”

Hattie started to respond when she heard a click and the phone went dead.

On August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify. With Tennessee’s ratification, the Nineteenth Amendment became law, ensuring that the right to vote could not be denied based on sex.

The ratification came in time for women to vote on November 2, in the 1920 Presidential Election.

__________

In the Fullness of Time: One Woman’s Story of Growth and Empowerment is available for purchase on Amazon in print, Kindle version, and on audio.

Purchase here.

Purchase here.

For additional information about the One-hundredth anniversary of women’s voting, see my former blog posts, such as

Women’s History Month–Valiant Women of the Vote,

One Hundred Years of Women’s Suffrage: February is a Big Month

Great-Soul Southern Suffragists: South Carolina Votes No

Telling the Story of One Hundred Years of Women’s Suffrage: Here’s Where We Stand

No Comments